In Season 1 of Cracking the Code, classic video games frequently serve as analogical springboards for discussing the challenges of high-speed guitar playing.

Centipede becomes a demonstration of three-note groupings in descending fours. Pac-Man and Robotron highlight two-hand synchronization problems. And the Atari 2600 and Intellivision home gaming consoles wage the war of elbow vs. wrist by proxy. The Eddie’s Arcade feature and lesson details an entire deleted scene that takes place in an abandoned arcade, with rows upon rows of arcade machines shrouded in noirish lighting, as an homage to Flynn’s Arcade in Tron: Legacy. And an early version of Season 1, Episode 3 even contained an animation using Donkey Kong itself — including rolling barrel triplets and a Mario death spin — which was eventually replaced with our more cohesive “Stringhopping War” mega-scene.

Our “Centipede” animation, demonstrating the 3nps groupings of descending fours. From Season 1, Episode 3.

Yes, the period-specificity of these games fits well with our visual style and historical narrative; homage to classic games is always fun to create. But it’s useful in an instructive capacity as well — the stylistic preponderance of metaphor-laden animations exists because those metaphors make it easier to understand abstract concepts related to guitar technique. And there are a lot of parallels between playing guitar and playing video games that we find really interesting.

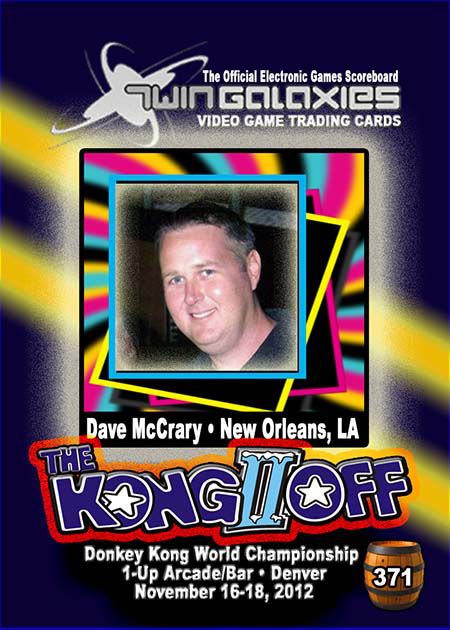

At the highest levels of performance, both types of play require elite capabilities, from physical coordination to mental stamina; rigorous practice regimens; and incredible consistency. When Dave McCrary emailed us about the show and casually dropped in the fact that he’s one of the best Donkey Kong players in the world, we jumped at the opportunity to learn more. We emailed Dave some questions about his experience as an elite-level DK player, and he graciously responded with an inside look at what it’s like to compete in the stratosphere of a classic arcade game, as well as some fantastic insights into the intersection of this experience with that of mastering the guitar.

So, tell us a bit about yourself — how did you get involved in the elite arcade gaming world?

I’m 42, a Professional Engineer at NASA in New Orleans, and I’m married with two step-children. I grew up in the age of video game arcades, which I was very addicted to, but that quickly changed to the home computer (Commodore 64) for programming and gaming, and in parallel my love for metal music and the guitar was starting. Once I saw the movie Crossroads in 1985, I was hooked on guitar and my path to learn the instrument began. Gaming slowly faded out and guitar started ramping up. I attended the University of New Orleans from 1989-1996 and received an Electrical Engineering degree. From there, work-life took over, guitar advancement plateaued (even though I played regularly still), and classic arcade gaming was in the past. Fast forward to 2007. I heard of the production of the documentary King of Kong, and when I finally saw it I was fascinated. Not just by seeing Donkey Kong again, but by the fact that there was this culture of people keeping Classic Arcade Gaming alive, along with websites where world records were tracked and forums to talk and meet others. Since the documentary focused on Donkey Kong, I wanted to try and see if I could do what the two stars (Billy Mitchell and Steve Wiebe) were doing on the game. So, my quest began.

What sorts of skills do you need, as a world-class Donkey Kong player, that might not be readily apparent to an outside observer?

Let me first start by saying that the majority of Donkey Kong is random. Being able to pattern a game, like Pac-man, is more about memorization and repeat performance, rather than reflexes and staying on your toes. This can be easily compared to someone playing a cover tune note-for-note vs. improvising a guitar solo. So, with Donkey Kong, it comes down to hardcore reflexes, quick recognition of a situation, being able to make a decision on the fly of how to handle what is coming at you, AND, at the same time, looking ahead, mainly with peripheral vision, to assess what is coming next.

How do you develop these skills? How often do you practice, and how long are your individual practice sessions? What’s the optimal training schedule for building these kinds of abilities?

Like most things in life, practice is the number one developer. Although I play on an original Donkey Kong machine, there exist emulations on computers now that allow you to actually save a section of your game and restart at that section and practice that section over and over again. This method of practicing is looked down upon by the hardcore enthusiasts who believe that it gives you an unfair advantage that wasn’t present in the past — just like Troy not having the right tablature and videos to help describe what was going on in the early 80’s. Learning guitar in the 2000’s is quite different now, as is learning Donkey Kong. I try to stay true to the classic tradition and mainly practice on the arcade only, which helps with learning and being comfortable with the controls.

The skills are developed by training yourself to not make the same mistake twice, and learning what you did wrong and how you would correct for it. Don’t get me wrong, the game is completely brutal in the beginning of the learning process — almost everything that happens to you, you swear there was no way out of that situation, or you think you DID press the button and it didn’t work, etc.

Being married and working, my basic practice schedule when I was at my highest part of learning was to come home from work, have dinner with the family, help the kids with their homework, and mainly have about 2-3 hours in the garage that evening to attempt to play. If you’re a master and can get a killscreen on donkey kong, the game takes about 2-2.5 hours to get to that point. But killscreens are rare occurrences, and once you get one, you are trying to point-press even more to beat your last personal best, so there are A LOT of restarts.

NOTE: A killscreen in Donkey Kong is the end of the game due to a programming error that doesn’t allow you to play level 22, you just die within 4 seconds. So basically the entire game (to world class players now) is about maximizing your points before getting to the killscreen. An average killscreen game will be about 850,000 points. A higher skilled player can achieve 900-950K. The upper echelon player can now break 1 MILLION and flip the score over. Only about 20 people have done this; I was the 4th person in the world to break 1 million in the history of Donkey Kong arcade. Now, the score to impress is 1.1 million. My high score is 1,091,400, just shy of 1.1M, but enough for me to still be in the top 10 all time in the history of DK high scores.

The optimal training schedule would be one that allows you to play basically all day, uninterrupted.

Just like with the guitar, a sufficient warmup session is always in order to perform all your best techniques. I still use the same Metal Method warmup session from the 80’s to this day to get my right and left hand in sync. The same goes for Donkey Kong — although it comes faster and faster now, making warming up less necessary, it’s always a good idea.

Is there a drink of champions for the Donkey Kong player elite?

Haha…I’m sure this answer is different for everyone. Not really any special drink, but as an adult, I’ve been known to have a glass or two of wine on the side when I play. It can help relax the nerves of certain situations in the game, but by no means is it a necessity. The 3 world-wide competitions I’ve been in, called The Kong Off — I don’t drink at these events. The last two were held in a bar room called the 1UP in downtown Denver, and we were given wrist bands for free drinks, so towards the end of the day I may have had a few beers.

Do you have any practice secrets or proprietary techniques? Or do you use commonly-known playing methods but simply execute much better than the typical player? Are there elements of technique — physical or otherwise — that couldn’t be reverse-engineered by watching a livecast of you playing?

One of the main reasons for the rise of Donkey Kong players is that a lot of us stream our games live. So, all techniques are shown to everyone. We even talk about it in the forums. (There is a forum website created called donkeykongforum.com. It has become bigger than we expected.) Knowing the technique is one thing, and it’s good not to hide it, it shows that it takes execution of skills to play the game, not a hidden magic secret.

I do have one skill that puts me above the others, and that is efficiency. I make sure I don’t stop moving or pause for any reason, I go up and down ladders with perfect precision, and I jump barrels while running, to keep myself moving towards my next area. Each board of Donkey Kong has a bonus time that drops 100 points about every second, so when you finish the board, after getting as many extra points as possible while playing, you have this extra bonus time. A player who can perform the same techniques as another world class player, but do it fast and flawlessly, can advance ahead.

At the first Kong Off in 2011, there were the top 11 players in the world, including the two from the documentary King of Kong. We started our competition with a speed run — who could get to the end of level 5 the fastest. Now keep in mind, if you die, you have to start that board over again. Well, this was my chance to shine, I was sitting next to current world record holder Hank Chien to my left and Billy Mitchell on my right. I was flying through the boards with my precision working for me…I even managed to die once and had to restart a board! But, turns out I was so far ahead that didn’t put me far behind. I noticed to my left I was close with Hank (who hadn’t died yet), and he got held up on a board, and I finished the opening contest first! It was just for a friendly $100, but it was the best feeling ever at the time to perform that well in front of everyone, and in front of the King of Kong stars, and to beat them also!

The idea of this “edge” applies so well in guitar as well: speed, accuracy and precision have been staple topics of almost every shredding teaching video. If I could “climb” a guitar scale with the same precision I climb a ladder in donkey kong, I’d be a much better player. I’m always jealous of a perfectly performed/picked climbing scale on guitar! Practice!

One thing I’ve noticed as I’ve perfected Donkey Kong is that I sometimes do useless tricks while playing because I can spare the movements and time. Guitarists love this advantage, to be so good on your instrument that you can perform little tricks to wow the crowd between measures of your song or solo — from a fancy slide, to tapping, to an acrobatic sling of your guitar over your neck. I love to bounce off walls in Donkey Kong to miss being hit by barrels; it saves my life and wows the crowd.

With the existence of the kill screen in the game, what does it take to keep upping your scores?

Nowadays, pushing the Donkey Kong score to new limits with a killscreen existing gets harder and harder. Think of it as a big rubber band. Just to get a killscreen you have to stretch the rubber band pretty tight. Now to repeat that performance and add another 50,000 to your score, you need to scrape points up along the way. There is a total of 117 boards in Donkey Kong over the 22 levels.

The further you stretch the rubber band, you can imagine how much harder it gets to add another 50,000 and stretch it even more. It’s exponentially harder. 1 million was once thought of as unreachable, but new point-pressing techniques were discovered to help break through. Basically, a point-pressing technique has to yield you more points than you are losing on the bonus timer. Otherwise, you’re spinning your wheels.

The masters in the documentary (in 2007) pushed the scores to the 1,060,000 range. There are currently about 10 arcade players with scores higher than that now. The current world record of 1,138,600 is held by a Harvard Plastic Surgeon, Hank Chien, with whom I’ve become friends over the years. And no one has yet beat Hank over the last 3 years.

One problem a lot of guitarists have is forgetting to chop things up into pieces and practice them methodically, perfecting the problem areas before putting a whole lick or song together. With an arcade game where you can’t just practice the toughest levels at will, how do you prepare for those hardest parts?

I agree wholeheartedly about breaking things into pieces and practice them methodically. However, I probably jumped ahead a little earlier by revealing that emulations exist that allow you to use save states to practice hard parts. I’m not an advocate of it, and I may have used it once or twice, but not nearly as much as some of my competition did for practice.

Donkey Kong is basically broken into two parts. Part one is Levels 1-4 where the game ramps up in complexity, but at the same time has more complex areas that the later levels do not. Then there are Levels 5-21 (with 22 being the killscreen). Basically getting to level 5 is what we call a “start”, because at that point difficulty has maxed out, and you just need to perform on the 6 boards per level until the end of the game.

The Atari vs. Intellivision console war — metaphor for the age-old “elbow or wrist?” conundrum. From Season 1, Episode 1.

But breaking things into chunks still plays a big part of the game, even without practicing the toughest levels. There are approximately 50 Barrel Boards in the game. To a world class player, the barrel boards are broken into four parts: the bottom hammer, getting to the top level where the next hammer is, grouping (a point-pressing techniques that allows score to be where they are now), and the top hammer. While you are playing each barrel board, you just want to get through each of those four parts. Now, if you don’t care about point-pressing, you can just go to the top and run through the boards, but your score will be very low. Anyway, approaching the four parts includes setting up the barrels some you can smash as many as possible with the hammer, and afterwards assessing the board to find your quickest way to the top with what barrels are coming down. Sometimes when I’m jumping barrels, I’m not even looking at Mario, I’m looking at the rest of the board to determine my next move. In guitar terms, you may be improvising a solo in A minor and the 8th measure is coming up and up know a switch to D minor is coming, so your subconscious lets you finish your A minor solo while you’re determining the best way (along with your feelings) of how to start the D minor solo. LOL, now feelings don’t play a part in Donkey Kong…or maybe they do. There are times when you might take an irrational leap of faith and survive. It yields you extra points, but at the same time you risk losing one of the only four men you receive in the game.

Have you ever had to rescue a woman in real life?

At first this question threw me a curve ball, but I quickly got the reference to saving Pauline in Donkey Kong. My wife always says I saved her when I let her move in after Hurricane Katrina. Her house was destroyed and we were just dating. She was evacuated in Houston with her mom and two children; our relationship could have easily faded away, but I asked her to move in with me since I didn’t flood. It was a move-in I wasn’t ready for since I’d had so much freedom for many years, but it did save her and the kids, and we are happy now.

Have you always been good at this sort of activity (whether games or something else that requires similar skills), or is it something you’ve picked up recently?

I think I always had good skills at problem solving, math, and performing well. Back in the day, I was one of the few who could solve a Rubik’s Cube. Even though I bought the book and memorized the steps, it was still impressive. Guitar was sort of like that — if you learned the song through a book, memorized it and re-performed it, you could impress a lot of people…up until Yngwie came along, and the guitar turned into an Olympic sport. It’s certainly a time I miss, the decade of the solo.

Are there any external factors that you notice influence or correlate with performance — like nutrition, sleep, or performance-enhancing drugs?

I’ve become so good at Donkey Kong that even if I’ve had too many drinks, I can still perform well for the majority of the game. However, one of the other classic arcade machines that I own and play well on is Missile Command. That game requires precise shooting and dealing with randomness on a different level, so alcohol and that game do not mix all. I do find that the few times I’ve tried a 5-hour energy while playing Donkey Kong my brain actually seems to function on a quicker level.

I just realized something I haven’t spoke of until this point, and I’m not going back to place it in the section of a specific thing I do when I play, but it’s worth noting: I always play with metal music on. It’s a necessity when I stream. The viewers love it, and the beats of the music actually put me in time with the machine. I force it to happen that way. Sometimes the last thing you want to do is press the jump button during a certain beat, because you can fly in the air at an unwanted time and die, but whenever it’s possible to press the button to keep up with the beat, I do it. It builds adrenaline with the game and puts me in an unbelievable zone. A zone that once you are knocked out can sometimes result in expletives flying out unwanted!

Remember, a full Donkey Kong game will only require 2.5 hours, so it’s not like preparing for a 48-hour arcade marathon game like Asteroids, which is a different style of playing and in no way considered superior over a Donkey Kong high score.

How does it feel to play in competition, as opposed to playing video games casually? What are the social dynamics of being a part of this community? Why do you compete?

The competitions are fun. At first I wasn’t sure about flying up to New Jersey from New Orleans just to play Donkey Kong, but I did it and finished in last place overall with my score! But I redeemed myself at Kong Off 2 and 3 with better performances. It’s not just a competition but a chance to see all the guys you talk to online, and meet more. I don’t consider myself an extrovert, but I’m not the typical stereotype of a computer introvert either. I love the attention of having someone watch me play. One thing I’ve regretted my whole life is never being in an official band — a garage band, or bar band. I hate that I didn’t do it, and I feel I let a great talent go to waste. The better and better I got on guitar I always felt I had more to learn, and wasn’t ready. I wanted to be so impressive when I got on stage, but time, work and life took over and just didn’t make it happen. I know it still can, though, and I look forward to having that feeling of playing music in front of others.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ibanez 777DY, 777LNG, 777SK, YJM Strat (custom made), 12 string acoustic, original 1989 RG 570. Sofa: Carvin thinline acoustic, Epiphone Joe Perry Les Paul, Ibanez Acoustic, and finally the EVH 5150.

And finally — tell us about your guitars! Any particular favorite instruments, amps, effects, or other gear? Do your game playing and your guitar playing influence one another in any unexpected ways?

Finally I get to talk about my guitars. Back in 1989 I bought my first real impressive guitar, a brand new Ibanez RG570. I played that guitar many years, and it wasn’t until 2003 that I started investing some of my engineering savings into musical instruments. Last year I kind of went overboard. Steve Vai’s Ibanez JEM777 was always my dream guitar, I loved the neon colors of the three original ones back in the day. I bought the yellow on eBay and it cost me a lot, then I found out about the rarity of the green JEM, the 777LNG. Only released in 1987, and only 777 made, all signed by Steve Vai. I told myself I would love to invest in one given that I could sell it for what I paid for it. I managed to come across one eventually — #179 out of 777. I have that one in a special display case. The only one I was missing was the Shocking Pink one. I never did find one so I decided to build and paint my own. It came out fantastic, and I used as many original parts as I could. I also built and painted my own YJM scalloped Strat, and an Eddie Van Halen 5150 Kramer. These are all shown here in my guitar collection picture.

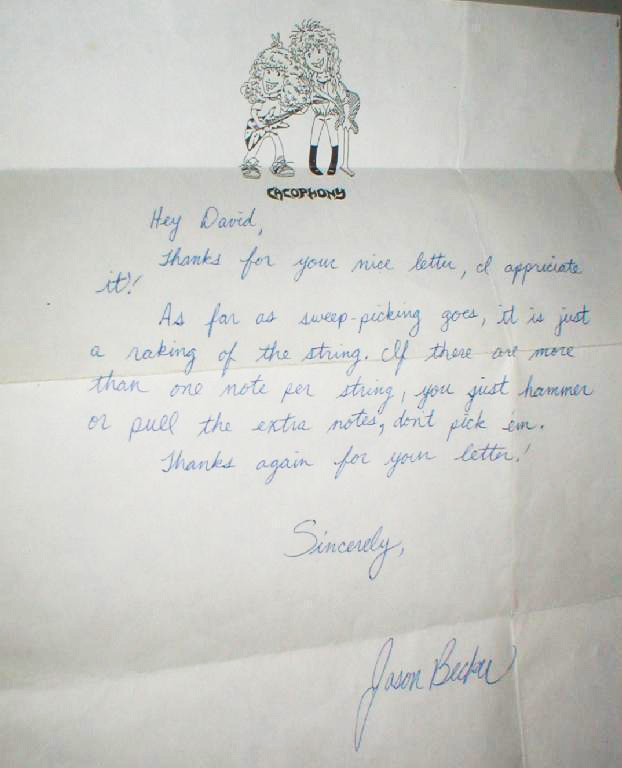

One other cool thing I have in my possession that reminds me of Troy’s adventures in Cracking the Code is a letter I wrote to Jason Becker back in the day before his ALS. I didn’t have a clue how Yngwie and Jason were doing arpeggios, so I wrote him and asked and he wrote me back this wonderful hand written letter. Given he cant move a muscle now, just seeing his handwriting to me is still a treat to look at. But, this was his response letter.

Anything else you’d like to add about the relationship between Donkey Kong and guitar?

One goal in Donkey Kong is to maximize your score, but the main thing is simply not dying! So every now and then you need to “bank” your points and just move on. Same goes for a improvised shredding solo — sometimes the most perfect solo can be one where the player knows when to stop and slow down, return to the melody and get back to pursuing the main goal. Basically, quit while you’re ahead.

Most guitarists learned the hard way that you can’t jump from Smoke on the Water to Bark at the Moon in one day. The same goes for Donkey Kong. A killscreen player thinks they’ve achieved the highest echelon only to find out they have a long way to go until 1.1 million. Jumping straight into the highest level techniques usually results in quick death or embarrassment. Guitarists can sympathize with that — we all know the view at the top of the shredding mountain will look and feel great once there, but take it slow. Press yourself, but not beyond your current abilities — keep climbing until you get there!