Got Caught Stealing Once, When I Was Five

Back when I was learning to play in the late ’80s, I used a Casio SK-1 to steal licks off records. For those who are not familiar with the SK-1, this thing was basically a miracle.

It’s a 31-note keyboard with a built-in sampling function. Press the “sample” button, and it would record exactly 1.4 seconds of whatever you threw at its little microphone. Pressing middle “A” on the keyboard played back the sample at actual pitch and speed. Press the next lower “A”, and you heard the sample one octave lower and at half-speed. And so on.

I didn’t initially intend to use the SK-1 as a guitar tool. I’m a keyboard player as well, and the commercials that ran during the Christmas season in 1986 floored me and my friend AJ, who also played keys: kid samples dog, plays dog songs on the keyboard, switches to piano sound, plays boogie-woogie improv. The built-in sounds were actually amazing — the piano in particular, which is usually a sore spot for consumer-level keyboards let alone bargain-basements finds like this one. I was immediately hooked. And at an astonishingly low price of $75, my parents were rendered defenseless to the covetous mewlings of their offspring.

The eureka moment came when I had just about grown weary of using the SK-1 to prank call teachers and the local McDonald’s with salacious moaning in four-part polyphony. On a whim, I recorded a snippet of an Eddie Van Halen lick and hit the low “A”. Instantly I knew how Anton Von Leeuwenhoek felt when he glimpsed the paramecium: a slow-motion world of crystal clear sonic detail I could previously only have imagined. Sure, 1.4 seconds isn’t a whole lot of time, but it was more than enough for most fast guitar parts. Copping licks became so easy, it wasn’t even a fair fight. The secrets of ’80s hair metal, which had been until then jealously guarded by their practitioners, were here laid bare and vulnerable before me. I began a campaign to systematically reverse-engineer the known guitar universe, 1.4 seconds at a time. First “Eruption” fell. Then the “Beat It” solo. Then Yngwie’s “Far Beyond the Sun”. Nobody was safe, not even Billy Joel’s “Root Beer Rag” and Ricky Scaggs’ “Country Boy”, from whence I lifted my first Scrugg’s-style banjo licks.

If it weren’t for the SK-1, I quite literally would not have half the chops I do now. The keys had a tendency to fall out like rotten teeth after a while (Bb was the first to go). Then AJ got the SK-5, which could record two samples for something like a total of three seconds each. Oh the decadence. But by then I was too drunk with riffage to care.

Sampling Redux

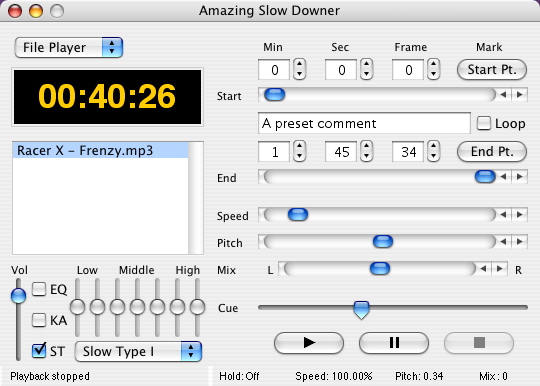

THE AMAZING SLOW DOWNER: And here you thought playing fast was amazing

Of course these days, mere sampling is passe and time stretching is de-rigeur. This is the practice of slowing the tempo of an audio track while keeping its pitch constant. Usually accomplished through the wonders of the fast Fourier transform, time stretching has found its way into a myriad of guitar-related products dedicated to just the kind of audio kleptomania I indulged in at an age when I should have been nicking Milky Ways from 7-Eleven instead. Many of these are hardware devices that combine porta-studio functionality with time stretching and looping. But when I feel the urge to beg, steal, and borrow someone else’s licks, I usually reach for a piece of software known humbly as The Amazing Slow Downer.

Despite being named after what sounds like a geriatric boxer, The Amazing Slow Downer is a serious transcription tool that excels in the range of slow-downing it permits. The Amazing Slow Downer‘s speed slider goes all the way from twice normal speed to one-fifth normal speed. The ASD‘s developers saw fit to include three slow-down algorithms, each suited to a particular kind or degree of time stretching. For shred work, I’m interested in getting the most amount of slow with the least amount of auditory crud, so I leave this switch set permanently to the mysterious “Slow Type 1”. No details are given as to the underlying time stretching techniques, but “Slow Type 1” provides intelligible output even with the speed slider pegged to its nadir.

As an example of the quality of the “Slow Type 1” algorithm at extreme settings, here’s a clip of me playing some Michael Angelo-style scalar ramblings:

The first thing you’ll notice about time stretching is that it has a way of transforming even fairly cool licks like this one into grating, fingernail-on-chalkboard-style torture exercises that seem to go on forever. True, you might not choose “Slow Type 1” to produce a Norah Jones supah-slow-jams mix tape for your next dinner date. But it does work well for dissecting unaccompanied guitar playing like this. Many classic Yngwie tunes, for example, include stop-time solo breaks which sparkle with clarity when processed with “Slow Type 1”. The Amazing Slow Downer’s magic formulas tend to degrade in proportion to the sophistication of the mix you ask it to process. Full-bandwidth arrangements with many instruments and frequent dynamic transients (e.g. cymbal crashes) suffer the most in this regard. But guitarists are lucky in that many ripe targets for this kind of analysis occur in high registers, comfortably above the din of the backing tracks. In such situations, “Slow Type 1” will aid you admirably in deciphering fast playing.

In addition to time shifting, the ASD also includes a pitch slider which allows me to fine-tune the source material to match my typically out-of-tune guitar, and the transport and looping controls are more or less intuitive. I’d love a dedicated rewind button, but similar functionality can be programmed via the preferences. The program also includes numerous keyboard equivalents for common transport events as well. All in all, The Amazing Slow Downer is an orgy of time stretching technology that makes my beloved SK-1 look like an Amish buggy.

Check Yourself

BEWARE OF THE DEVIL: Or join him. Did a deal down at the crossroads turn Chris Impellitteri’s technique from broken to bitchin’?

Aside from aping your idols, the most valuable use of time stretching technology is to check your own playing. If you’re the kind of person who only gets busy with the lights off, you’re not going to like this part. But the truth is, if you can’t play something without making mistakes, then you need to admit to yourself that you really can’t play it at all. A classic and rather interesting example of this can be found in the development of one of shred’s most able practitioners: Chris Impellitteri.

In 1989, Chris released a video called Speed Soloing through pioneering instructional guitar producers REH Video. Popular at the time, the video eventually became notorious for its egregious display of picking faux pas. In a previous version of this article, I had pulled a clip from Speed Soloing as an example of what happens when your hands rudely flout your best intentions at high metronome settings. Here’s the clip:

If you’ve spent any time surfing shred-related web sites and discussion forums, you’ve no doubt heard a lot of playing like this. The problem here is frequently cited as one of hand coordination, i.e. the left hand is moving fast, the right hand is moving fast, but they’re not in synchrony. In reality, the problem is more specific than that: advanced players use a specific combination of hand motions to get from one string to another cleanly, and at this point in his career Chris had not yet developed those motions. Instead, he’s practicing a formula most of us probably considered early on as well — namely, the brute-force method of playing super fast with both hands and hoping it all just, kinda, works out somehow. It’s a tidy fantasy, but unfortunately only a fantasy. If each pick stroke is not mated with exactly one note in the left hand, it’s not going to sound convincing. While The Amazing Slow Downer will reveal the true extent of the cacophony, experienced players can spot faux-shred even without time stretching from a mile away. Similarly, even without time-stretching, it’s sonically evident in the example above that something’s amiss, even before we slow it down.

Re-Chris(t)ening

In the original version of this article, my citation of the Speed Soloing example was intentionally anonymous — not a critique of Chris, just an available and illustrative example of a nearly universal issue in developmental technique. Nevertheless, a number of readers picked up on the source of the audio allusion, and construed it as a subtle dig. Not at all. In fact, from my perspective as both player and fan, Chris is an interesting case. For one thing, not all aspects of Chris’ playing on Speed Soloing were in need of remedial attention. Many licks, notably the pentatonic and arpeggiated chicken-picking examples, were tight on the money. The issue was specifically one of three-note-per-string alternate picking, and it was present on the 1987 Impellitteri EP as well as on its successor, 1988’s Stand in Line. Speed Soloing followed suit in 1989. Then, in the ’90s, a curious thing happened. It disappeared:

The clarity of Chris’ picking is more than evident in this example, sampled from the track Walk Away, off Impellitteri’s 1996 release Screaming Symphony. In fact, things started getting better as early as 1992’s Grin and Bear It. And not just a little better — a lot better. Better enough, in fact, that Chris was voted the second-fastest shredder of all time in a popularly-quoted compendium in Guitar One Magazine. Cheeky though the article’s tone may be, it is nevertheless the case that Chris is currently among the most well-respected names in pick mechanics.

So this is quite an interesting development. I once asked Rusty Cooley what he though had happened to Chris in the interim, and he responded simply: “He practiced.” Well yes, and no. Databases at Google are no doubt stuffed full of the web pages of dedicated players doing daily battle with the same demons that beguiled Impellitteri in his early years. Yet the vast majority of these players never prove able to surmount the challenge, let alone rise to the ranks of the cleanest of all time. Spend even a few minutes time stretching your own material, and you’ll realize just how hard it is to play things perfectly at high speeds. Easy licks will grow all kinds of barnacles from stray picking and fretting hand movements, and hard licks become junkyards of metallic clang. By contrast, clean playing sounds clean both at high speeds and under high-powered magnification.

So hats off to Chris Impellitteri, who passes the time-stretch test with flying colors, and serves as a beacon for all in the battle with the dark lord of discontinuity. My film project, Cracking the Code: The Secrets of Shred Guitar will explore in great detail the mechanical steps taken by master players to vanquish the demons of slop.

Slow Healing

You’re just not cut out for the Brawny paper towels label until you’ve subjected your own riffing to the unflinching scrutiny of time shifting. Do the following: Record your best lick, slow it down, and count the errors. Whether you use a modern time stretching tool like The Amazing Slow Downer, a sampler like the Casio SK-1, or the audio equivalent of two flints and some dry leaves, like a variable-speed tape recorder, it doesn’t matter. What’s most important is that you actually ask the hard questions about your own playing. Do you hear exactly one cleanly articulated pickstroke per note? Or do you hear something that sounds like the theremin solo in Whole Lotta Love?

If you avoid this trial, thinking nobody will notice, think again. A sloppy lick at high speeds may fool novices, but it will not impress experienced players. And it will sound downright embarrassing slowed down. The Amazing Slow Downer costs a measly $40, which means that a kid with a Dimebag Darrell signature model and a paper route will soon be picking your playing apart as surely as if you had emailed him the tablature yesterday. You can rest assured, however, that marquis talents like Vai, Malmsteen, Impellitteri, Gilbert, Angelo, Moore, and others are spotlessly clean, even under close forensic inspection. This is of course one of the many reasons they deserve every bit of the adulation they receive. And why it takes a lot of slow listening to get to that level.